The Zionist guns trained in our direction were not a mere physical barrier: they were a lethal reminder that our city, for us, was to be now no more than a memory; a dream that we were now back to zero. Enjoy the view if you can, in the midst of the homeless thousands. But you’ve been plucked out by the roots. Your books, your ideas, your visions: they’re absurd indicators to a world where the absurd rules supreme.

--Jabra Ibrahim Jabra[1]

Perhaps the most striking feature of Israel’s effort to construct an undisputed history, territoriality and identity in Palestine is its banality: the banality that often comes with the normalisation of the absurd. A state of conscious or unconscious denial is necessary to go on living with oneself whilst knowing of the situations of gross injustice taking place. The routine Israeli tactics of replacing one historical narrative with another and displacing multiple layers of memories with a single undisputed linearity are now well-known, and have been carried out by way of a paradoxical formation of secularized nationalist yet simultaneously Jewish cultural institutions, discourses, icons and metaphors effecting the obliteration of the pre-1948 Palestinian fabric. These are but a few instances of the convoluted construction of a precarious identity in the modern Israeli State. Until quite recently, the somewhat predictable practices of cultural exclusion and military domination have largely gone unacknowledged in the international community, as too have the more commonplace bureaucratic hurdles and procedures aimed at maintaining a costly occupation in the Occupied Territories and the simultaneous control of the lives of the Palestinian citizens of Israel under a carefully designed system of legalised, institutionalised and indeed normalised racial discrimination. Yet, underlying these practices of domination, in Israel there exists a certain self-representation to itself and to the global community that rests on a deeply-held narrative: that a civilized and western Jewish state was indeed liberated from Arabs by Holocaust survivors against all odds in 1948, at odds with the narrative of the forcible expulsion of Arabs by colonial settlers, armed with the latest European military technology and racist ideology.

More perilous than this incongruity of representation, however, is the way in which the violent structures of domination and control practiced by Israel engender in those citizens witnessing them what criminologist and sociologist Stanley Cohen once described as ‘states of denial’. Cohen makes reference to the modes of avoidance practiced by those acting and living with the knowledge of crimes taking place, in order for them to continue to do so.[2] The instances to build a so-called civilised, liberal and progressive nation on the ruins and pain of another people are countless: from demolished historical Palestinian villages turned progressive artist communes, such as the notorious Ayn Hawd in Haifa, to plundered grand Palestinian homes redistributed to house new Jewish immigrants to Israel, to urban spaces such as the old heart of Jaffa’s port, redeveloped as a tourist playground and now brimming with high-end restaurants and art galleries run by Jewish Israeli entrepreneurs. Standing in the Holocaust History Museum in Vad Yashem, one gets a breathtaking panoramic view of an absent-yet-present emblem of Palestinian pain, the village of Deir Yassin. There are no markers, placards, or memorials, and no mention from tour guides in the museum regarding what their visitors see from where they stand. “By the end of the 1948 war,” writes Walid Khalidi in All That Remains, “hundreds of entire villages had not only been depopulated but obliterated; travellers of Israeli roads and highways can see traces of their presence that would escape the notice of the casual passer-by: a fenced-in area, often surmounting a gentle hill, of olive and other fruit trees left untended, of cactus hedges and domesticated plants run wild. Now and then a few crumbled houses are left standing, a neglected mosque or church, collapsing walls along the ghost of a village lane, but in the vast majority of cases, all that remains is a scattering of stones and rubble across a forgotten landscape”.[3]

Enter Uriel Orlow’s multi-part Unmade Film. This impossible film – this not-yet-made film, this fragmented film that never fully becomes one, despite its “plan” to do so – has been emerging over an extended and ongoing period of research and production that excavates multiple narratives and layered meanings that converge in Deir Yassin. Yet by never actually being realized, Orlow’s Unmade Film reconstructs a narrative of space, time and historical blind-spots that adds layers of unsettled new meaning to questions of subconscious pain, trauma and suffering in the contexts of obliterated geo-histories.

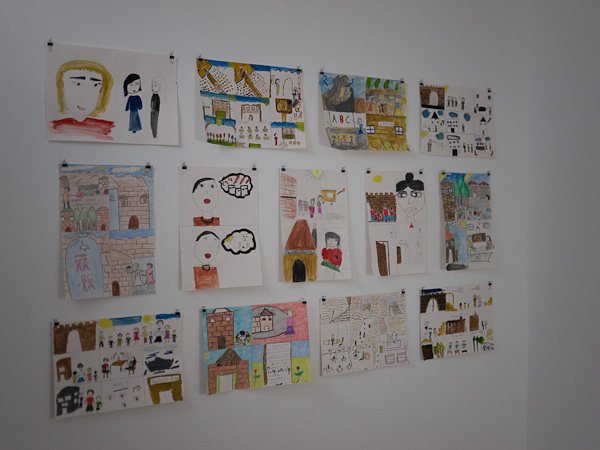

[Uriel Orlow, "The Storyboard" (2013). Drawings by pupils from Dar Al-Tifel Al-Arabi, Jerusalem. Courtesy of the artist.]

[Uriel Orlow, "The Storyboard" (2013). Drawings by pupils from Dar Al-Tifel Al-Arabi, Jerusalem. Courtesy of the artist.]

Deir Yassin and what remains of it, like the overall landscape Khalidi describes, is conspicuously absent. Despite the banality of the systemic violence it is a part of, Deir Yassin more so than other razed villages continues to haunt the existence of all those implicated in its fate, whether knowingly or not. “Remember Deir Yassin”, Haganah Radio broadcasts screamed out in warning to force more villagers from other villages to leave their homes.[4] Deir Yassin today is, and has been since 1948, materially absent, as there are no physical reminders of it – save, ironically, for the remaining stone houses left behind after the massacre that today form the mental institute Kfar Sha’ul, initially opened to treat victims of the Holocaust in the early 1950s. The village has also literally been ruptured from the mental geography of a whole generation of Palestinians who are barred from entering Jerusalem as a result of Israeli segregation policy, which has severed Palestinians from each other and from Israelis since the onset of the second Intifada. The 1948 confiscation of hundreds of Palestinian villages in their entirety is often also missing from mainstream western scholarly and even non-scholarly literature on tragedy, loss and trauma. Yet even in its immaterial form, the village of Deir Yassin is lodged in Palestinian sub-consciousness and offers a compelling site for the excavation of competing and shifting significations, along with meanings of the cruel act of dispossession and the life that follows it.

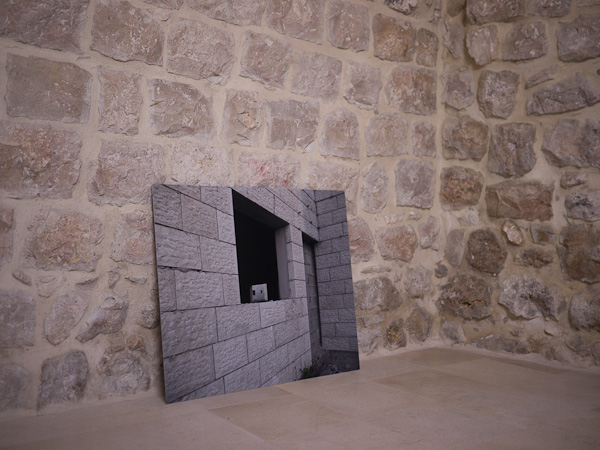

[Uriel Orlow, "The Reconnaissance" (2012-13). Installation including slide projection, mounted photographs and sound. Courtesy of the artist.]

[Uriel Orlow, "The Reconnaissance" (2012-13). Installation including slide projection, mounted photographs and sound. Courtesy of the artist.]

[Uriel Orlow, "The Reconnaissance" (2012-13). Courtesy of the artist.]

[Uriel Orlow, "The Reconnaissance" (2012-13). Courtesy of the artist.]

Confronting this tragic conundrum, Orlow works his way up from intimate childhood memories of travelling from Europe to visit his great aunt, who lived in Kfar Sha’ul for some 30 years after her arrival to Jerusalem and her survival of Auschwitz. His work boldly locates within the history of European racism the psychological dispute that so much defines Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians, and shows how the fate of the two are intricately entwined. While this conclusion screams at us from the performances, open and closed spaces, buildings, posing bodies, spoken words, texts and images that the work makes use of, it is not the main point Orlow intends to make. Upon the horrific realization that Kfar Sha’ul is in fact Deir Yassin, Orlow set out on a journey to probe the meaning of one painful event in history obliterating the other, in a context of historical intimacy between both. Bent on provoking the Israeli blind-spot of Deir Yassin through never finalising the making of his film – a film that never closes its circle of production – Orlow unequivocally re-articulates the history of the massacre as a contemporary event and an ongoing phenomenon. Orlow centres on the polysemic manifestations of tremors that remain after shock. This is articulated through the various components of which the ‘film’ is comprised: for instance, in the case of "The Voiceover," a reconstructed audio narrative is pulled together from various investigations, site visits, conversations with nurses at the hospital, historians and actual survivors of the massacre at Deir Yassin now living in nearby villages; or through the images that comprise "The Staging," a workshop that was undertaken in order to produce a joint tableau vivant, which mixes notions of the everyday with the lunacy of the violence that continues to haunt the contemporary lives of the participants. What transpires from the entirety of the Unmade Film in all its different components is a cathartic poetic: one that is visceral in form, and categorically rejects the absurdity of violence and the banality it relies on.

[Uriel Orlow, "The Staging" (2012-13). Courtesy of the artist.]

[Uriel Orlow, "The Staging" (2012-13). Courtesy of the artist.]

[Uriel Orlow, "Score for an Unmade Film in Memory of Deir Yassin" (2013). Image from a concert at Sakakini Cultural Center, Ramallah, April 9, 2013. Courtesy of the artist.]

[Uriel Orlow, "Score for an Unmade Film in Memory of Deir Yassin" (2013). Image from a concert at Sakakini Cultural Center, Ramallah, April 9, 2013. Courtesy of the artist.]

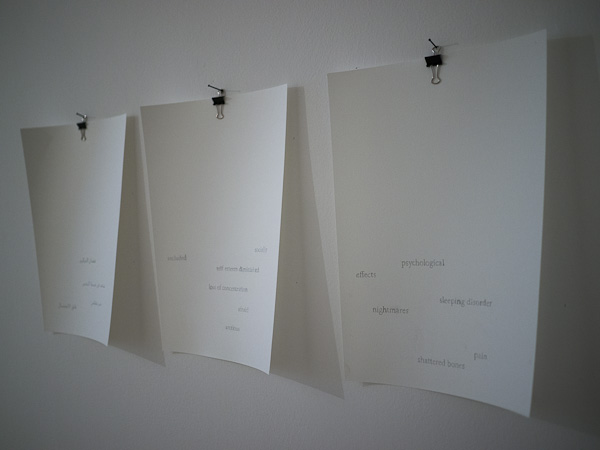

For those excavating contexts where memory-making is comprised of antagonistic identities and contentious sites of struggle, the fixation on memory goes beyond the mere distrust of history to ever truly represent itself. It also reveals the obsessive fear of forgetting, and reminds us that memory embodies the very force of life itself. But Unmade Film goes a step further than uncovering an obliterated site of memory in order to go on living; by reconstructing a historical, temporal and spatial narrative already etched into Palestinian minds and nestled in their subconscious, Orlow captures the mysteries and rhythms and above all the haunting of an unresolved past, simply by juxtaposing them with the present, thereby showing us that they are essentially one and the same. In content and form, the project’s inclusive nature is defined by its production of a set of collaborative artistic practices and draws much of its novelty from its unflinching reliance on close cooperation with descendants and survivors of Deir Yassin, current-day prisoners, health workers, as well as other artists and musicians. Orlow insists on a processed-based approach, as opposed to a finished and finite artwork. In its making the work connects to the incessant formation of a collective consciousness in Palestine, even in the face of fierce attempts to eliminate it. In one work, viewers can engage with the descriptions of symptoms of the policies of occupation extracted from case studies gathered by the artist through an ongoing dialogue with mental health-workers at Palestinian psychiatric counselling centres in Jerusalem and Ramallah. "The Script" – shown as a series of slide projections or handwritten text – displays elliptical references to psychological trauma such as “alienation, anxiety, low self-esteem, repeating nightmares” or “lost sense of purpose, screaming unexpectedly, separation anxiety”. Such text compellingly recalls the representation of trauma and psychiatric disturbances historically present in Israeli art and especially film production. Ironically, the text also takes us back to the point of inception of Kfar Sha’ul, set up to treat these same symptoms of another crime in another place. By way of drawing this existentially uncomfortable parallel, Orlow guides his spectators to the very core of Israeli identity itself, as if to subtly provoke the absent-yet-present blind-spot that is Deir Yassin.

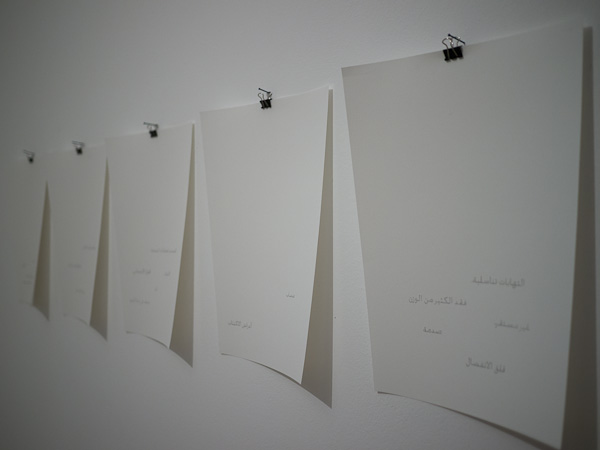

[Uriel Orlow, "The Script" (2013) Courtesy of the artist.]

[Uriel Orlow, "The Script" (2013) Courtesy of the artist.]

[Uriel Orlow, "The Script" (2013) Courtesy of the artist.]

[Uriel Orlow, "The Script" (2013) Courtesy of the artist.]

The plan is that Un-made Film will end with "The Closing Credits": a short 16mm film of text-scroll with all the names in Arabic and English of the depopulated villages of 1948 on a background of filmed ground. As such, the work adds a visual component to the growing canon of literature that is documenting, archiving and, most significantly, re-reading the loss of historical Palestine and how we think of Israel’s relationship to Palestinians today. But Orlow’s comprehensive, fierce yet subtle delving into the multiple layers of this history of violence through the obliterated site of Deir Yassin which paradoxically remains alive by way of the lives it haunts, adds a new dimension to how this is to be intellectually, spatially, temporally and emotionally expressed. For the work is, besides all that it is, an urgent plea to attend to historical discontents and their seemingly impossible antidotes by looking at that which haunts us straight in the face.

[1] Jabra I. Jabra, "The Palestinian Exile as Writer" in Journal of Palestine Studies, vol. 8, no. 2, Winter 1979, pg 78.

[2] Stanley Cohen, States of Denial: Knowing About Atrocities and Suffering (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2001).

[3] Walid Khalidi, ed., All that Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel (Washington D.C: Institute for Palestine Studies, 1992).

[4] Ariela Azoulay, From Palestine to Israel: A Photographic Record of Destruction and State Formation, 1947-1950, tr. Charles S. Kamen (London: Pluto Press, 2011) p. 160.

This essay first appeared in Uriel Orlow: Unmade Film, published by edition fink, Zurich on the occasion of the eponymous exhibition at Al-Ma`mal Foundation for Contemporary Art Jerusalem (2013) and is reprinted with permission of the author and the artist.